Tribal sovereignty is at risk; the meaning of the Castro-Huerta decision.

Tribal sovereignty is once again under attack. In the U.S. Supreme Court opinion Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, the Court decided that States could now gain criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country that at one time been left to Tribal courts and the Federal government. This opinion contradicts previous treaties, laws, and specifically a recent court ruling and in the most egregious way lays the groundwork for states across the nation to change the criminal jurisdiction that is decided on sovereign land.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 5-4 decision in Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, flouted centuries of precedent and clear commitments to tribes from the federal government in holding that states exercise concurrent criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country involving non-Indian perpetrators and Indian victims. The Castro-Huerta decision is devastatingly corrosive to tribal sovereignty. It further complicates criminal jurisdiction and endangers the lives of Indigenous people in Indian Country. Moreover, the decision represents the Court playing political games with tribes to appease the lies and disinformation of Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt and unelected Attorney General John O’Connor; and in the process subsequently jeopardizes hundreds upon hundreds of sovereign nations within the lands known as the United States, including those in Montana. This decision signals also signals the Court’s ignorance of federal Indian law and policy and signals that no aspect of tribal sovereignty of Indian law is safe.

Since time of first contact, states have been no friends to Tribes or to Indigenous people, and have demonstrated neither the willingness nor commitment to address the public safety needs of Indigenous communities. In fact, the Castro-Huerta decision comes in the aftermath of a sustained, racist disinformation campaign against the Court’s ruling in McGirt v. Oklahoma (2020), which found that Congress never disestablished reservations in Eastern Oklahoma and for the purposes of criminal jurisdiction those lands remained Indian Country excluding Oklahoma’s jurisdictional claims. The McGirt decision was a major victory for Tribal Nations and Indigenous people across these lands.

In Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, Victor Manuel Castro-Huerta, a non-Indian who had been convicted by the state in 2017 of child neglect of an Indigenous child while living in Tulsa County, challenged his sentence on the grounds that the state lacked jurisdiction to convict him. Flying in the face of hundreds of years of federal Indian law, and indeed in direct contradiction to the 2020 McGirt opinion, the Supreme Court held that states have jurisdiction to prosecute non-Indian defendants who commit crimes against Indians in Indian Country.

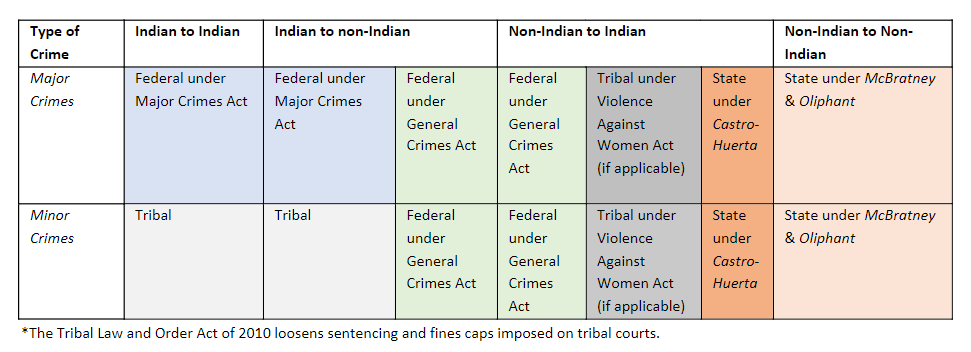

Criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country is convoluted. The process of investigating, trying, and punishing individuals over alleged offenses is complicated by a series of federal statutes and court decisions intertwined with the settler-colonial history of the United States. Over time the courts eroded the inherent sovereignty of Tribes and stripped their ability to address harms within the community.

Currently in Indian Country, federal, state, local, and tribal agencies operate policing forces, court systems, and carceral centers—creating a labyrinth of criminal jurisdiction, where any one or multiple agencies may oversee any given offense depending on the circumstances. This system is highly perplexing for anyone trying to navigate and apply criminal law, and ultimately illuminates the potential violence and precarity of Indigenous lives in Indian Country. Castro-Huerta complicates this matrix by permitting states to exercise criminal jurisdiction in a subset of criminal cases involving non-Indian perpetrators to Indian victims further destabilizing the inherent sovereignty of Tribal Nations, and endangering the lives of Indigenous people.

The decision creates a quagmire. One that is not only difficult to understand and implement in Indian Country, but additionally provides unprecedented power to states to prosecute crimes in Indian country. Furthermore, it circumvents the process laid out in Public Law 280, a law which in 1953 transferred criminal jurisdiction to six states (with limited exceptions) and subsequently, created a process for “optional” transfers upon the consent of the tribe.

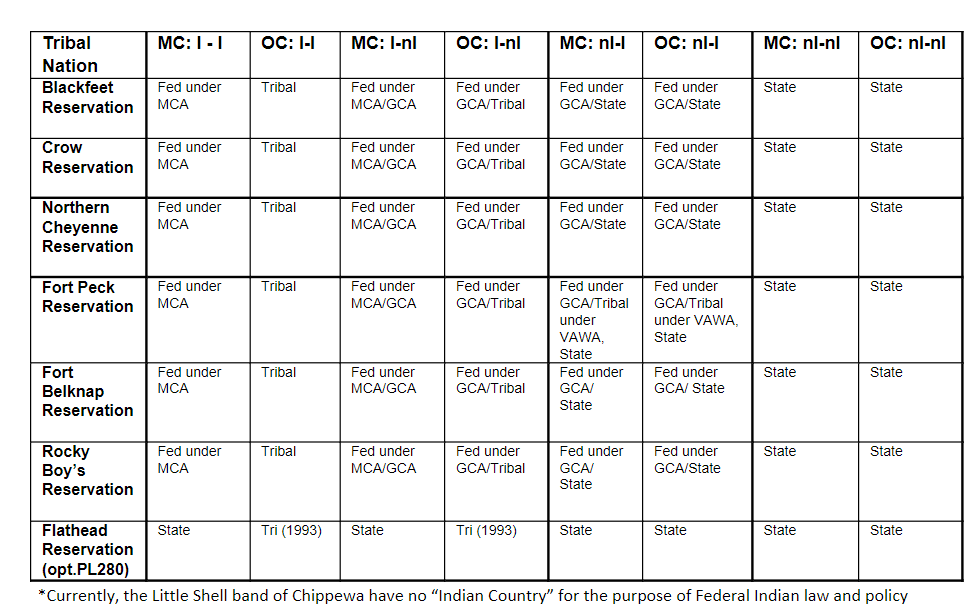

Montana became an optional-Public Law 280 state in 1963, where the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT) were the only nation to opt-in—resulting in the state of Montana subsuming criminal jurisdiction on the Flathead Reservation. However, only two years into the agreement, CSKT sought to end the arrangement. Though initially rebuffed by state officials, by 1993, CSKT forged an agreement with the state around exclusive jurisdiction of misdemeanor crimes by Indians and in 2017 with SB 310, the Flathead’s jurisdiction schema may soon look different.

Notwithstanding the CSKT, Montana’s other Tribal Nations function under the chart shown above where different sovereigns exercise criminal jurisdiction on tribal lands. It’s important to note that on top of that, entirely different systems of sovereigns function within Montana. Castro-Huerta adversely impacts the inherent sovereignty and ability of the other six nations to exercise criminal jurisdiction. From Blackfeet to Northern Cheyenne all the way from the Chippewa-Cree down to Crow, their ability to keep themselves safe has been impacted. In inviting states to exercise criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country in a subset of cases, current policing agencies such as state police, tribal police, Bureau of Indian Affairs officers, Federal Bureau of Investigation agents, and numerous other entities may arrive on the scene, need to assess the nature of the crime – major or other – whether the perpetrator(s) or victim(s) are Indian or non-Indian before continuing any investigations. An already tangled web just added another layer.

Indigenous Montanans, no matter where they live, confront a criminal legal system in this state committed to forgetting about, killing, immiserating, and incarcerating. Indigenous people compose ~7% of the state’s population, but currently 28% of its missing, throughout the United States, Indigenous women are 38 times more likely and, men 14 times, to be killed by police (than their white counterparts), and compose ~7%, but 25% and 22% of the state’s jail and prison population respectively.

We have been thrust into unimaginable territory, but the ACLU of Montana continues the fight, alongside the Indigenous people of Montana, for tribal sovereignty and will not back down from this egregious, harmful decision. Many of us know that this is not the first time the Supreme Court has tried to subvert the inherent sovereignty of Tribes, and especially the right to exercise criminal jurisdiction. Similar efforts have been fought by ancestors and the current generation of Indigenous people in cases such as United States v. Kagama (1886), Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe (1978), and Duro v. Reina (1990).

Justice Gorsuch, in his blistering dissent to the Court’s decision in Castro-Huerta, essentially called on Congress to rectify this decision as has been done with the “Duro fix”, which recognized the Tribes’ ability to prosecute non-member and member Indians, and the “partial Oliphant fix” which created a process and ultimately the ability to prosecute non-Indians for certain domestic violence crimes against Indians. Congress must now act again, with an unwavering commitment to the self-determination of Indigenous people, to recognize the inherent sovereignty of Tribal Nations to exercise criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country. Otherwise, Indigenous people in Indian Country, including those in Montana, will wake up in nations with less sovereignty, less ability to keep each other safe, and more confusion, harm, and violence.

We are still here and here we shall remain.