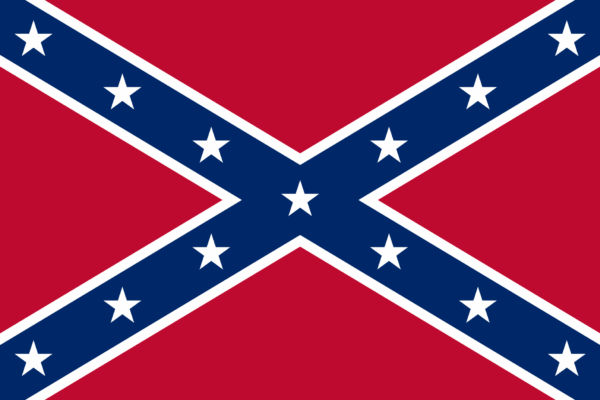

A recent incident at Park High School in Livingston, in which students flew Confederate flags from their trucks shortly after a black student enrolled, offers an opportunity to reflect on the extent of students’ right to engage in offensive speech at school.

The United States Supreme Court has repeatedly acknowledged that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” For example, in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, the Supreme Court held that it was unconstitutional for public school officials to punish students for wearing black armbands in silent protest of the Vietnam War.

Schools’ hands are not completely tied when it comes to prohibiting controversial speech, however. Tinker recognized that some limitations on student speech are allowed in the school setting that would not be permissible outside the school’s boundaries. First, schools may prohibit speech that impinges on the rights of other students, including their rights to be secure and to be let alone. Second, schools may prohibit speech that causes a “substantial disruption or material interference with school activities.”

At Park High School, the Confederate flags were flown on school grounds after a black student – the only black student at Park High School – had begun attending. At least one student admitted that he flew the flag specifically to express his negative views of black people. The school, which does not have a general policy categorically banning the Confederate flag, banned it for the rest of the school year in response to this specific incident. That response is consistent with the school’s authority to ban speech that interferes with other students’ safety and well-being.

The Confederate flag has historically been a symbol of racial hostility. In this case, that is precisely why at least one student displayed the flag. There is no constitutional problem with the school protecting its sole black student from abuse and intimidation.

A few notes of caution are in order. Just because student speech is controversial, or even offensive, to some does not mean that it meets one of the Tinker exceptions. As the Supreme Court stated in Tinker, the fundamental values of a democratic society “include tolerance of divergent political and religious views, even when the views expressed may be unpopular.” And where student speech does not curtail the rights of other students to feel safe or be let alone, the mere fact that other students react strongly to it does not justify punishing the speaker. For example, if a student flies a rainbow flag from her car in support of LGBT rights, that student should not be punished if another student chooses to burn her flag. Likewise, if a student displays an NRA bumper sticker on his own car, he should not be punished if someone else vandalizes the car in response to the sticker.

Schools are learning environments where no topic should be declared categorically off limits. Indeed, one would hope that Park High School would use this occasion as a teachable moment. Students should learn about and discuss why the Confederate flag’s mere display is so deeply offensive and incendiary. While banning the flag may have been necessary and justified in this instance, the long-term solution to what happened in Livingston is to address the insensitivity that led to it in the first place, and to educate students about the importance of racial diversity and mutual respect for those of different backgrounds.